New Map Reveals Ships Buried in SF

New Map Reveals Ships Buried in SF

Dozens of vessels that brought gold-crazed prospectors to the city in the 19th century still lie beneath the streets as detailed in a National Geographic article.

Every day thousands of passengers on underground streetcars in San Francisco pass through the hull of a 19th-century ship without knowing it. Likewise, thousands of pedestrians walk unawares over dozens of old ships buried beneath the streets of the city’s financial district. The vessels brought eager prospectors to San Francisco during the California Gold Rush, only to be mostly abandoned and later covered up by landfill as the city grew like crazy in the late 1800s.

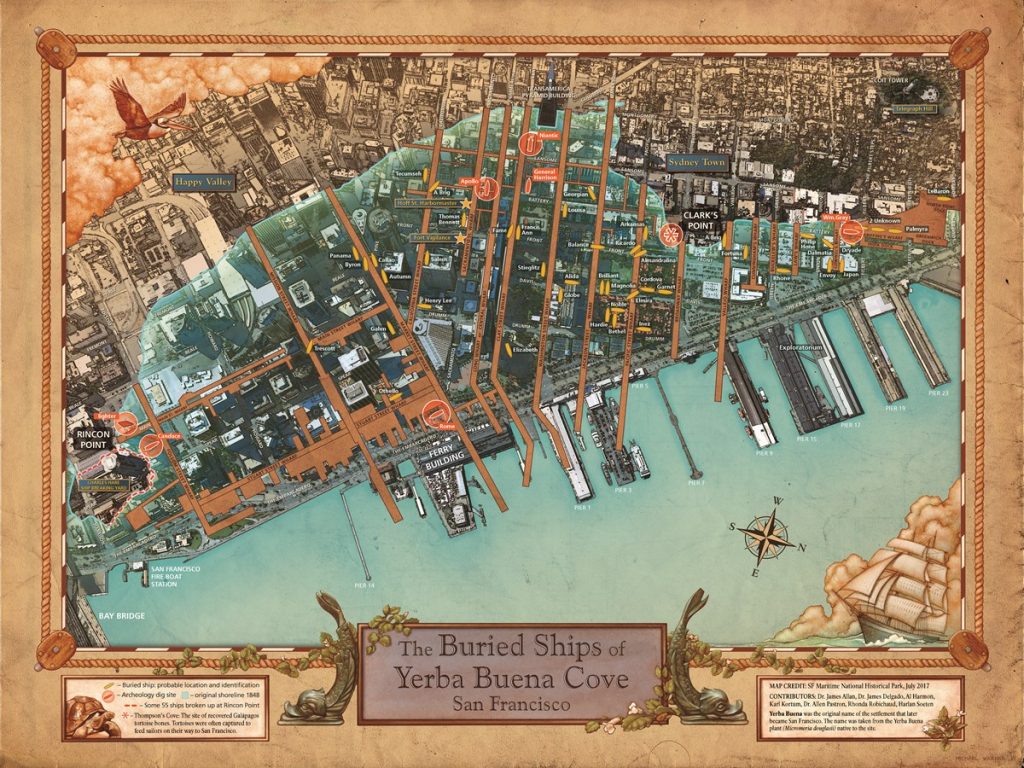

Now, the San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park has created a new map of these buried ships, adding several fascinating discoveries made by archaeologists since the first buried-ships map was issued, in 1963.

It’s hard to imagine now, but the area at the foot of Market Street, on the city’s eastern flank, was once a shallow body of water called Yerba Buena Cove, says Richard Everett, the park’s curator of exhibits. The shoreline extended inland to where the iconic Transamerica Pyramid now rises skyward.

In 1848, when news of the Gold Rush began spreading, people were so desperate to get to California that all sorts of dubious vessels were pressed into service, Everett says. On arrival, ship captains found no waiting cargo or passengers to justify a return journey—and besides, they and their crew were eager to try their own luck in the gold fields.

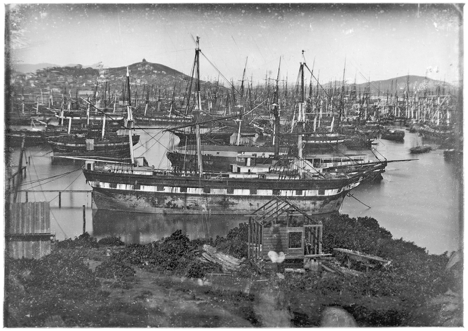

This is one of five panels in a panoramic daguerreotype taken by William Shew in or around 1852. Rincon Point, the southern end of the cove, appears in the foreground.

The ships weren’t necessarily abandoned—often a keeper was hired to keep an eye on them, Everett says—but they languished and began to deteriorate. The daguerreotype above, part of a remarkable panorama taken in 1852, shows what historians have described as a “forest of masts” in Yerba Buena Cove.

Sometimes the ships were put to other uses. The most famous example is the whaling ship Niantic, which was intentionally run aground in 1849 and used as a warehouse, saloon, and hotel before it burned down in a huge fire in 1851 that claimed many other ships in the cove. A hotel was later built atop the remnants of the Niantic at the corner of Clay and Sansome streets, about six blocks from the current shoreline (see map at top of post).

A few ships were sunk intentionally. Then as now, real estate was a hot commodity in San Francisco, but the laws at the time had a few more loopholes. “You could sink a ship and claim the land under it,” Everett says. You could even pay someone to tow your ship into position and sink it for you. Then, as landfill covered the cove, you’d eventually end up with a piece of prime real estate. All this maneuvering and the competition for space led to a few skirmishes and gunfights.

One of these intentionally scuttled ships was the Rome, which was rediscovered in the 1990s when the city dug a tunnel to extend a streetcar line (the N-Judah) south of Market Street. Today the line (along with two others, the T and the K) passes through the forward hull of the ship.

Cartographers are still putting the finishing touches on the new map, which will appear in the visitors’ center at the San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park.

Eventually Yerba Buena Cove was filled in. People built piers out into it to reach ships moored in deeper water, Everett says. “The wharves are constantly growing like fingers out from the shore.” Then people began dumping debris and sand into the cove, which was only a few feet deep in many places to begin with. “By having guys with carts and horses dump sand off your pier,” Everett says, “you could create land that you could own.”

It was a land-grab strategy with lasting ramifications—as evidenced by the ongoing controversy over a sinking, tilting skyscraper built on landfill near what was once the southern edge of Yerba Buena Cove.

Three archaeologists—James Allan, James Delgado, and Allen Pastron—consulted on the making of the new shipwreck map, and discoveries by them and their colleagues have added several fascinating details that weren’t on the original buried-ships map created by the San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park in 1963 (see below). Red circles on the new map indicate sites that have been studied by archaeologists.

This detail from the original 1963 buried-ships map shows “Sydney Town,” where Australians congregated in Gold Rush days. There was a Chilean enclave just inland from here, and fights sometimes broke out between the two groups.

One of the most interesting additions to the new map is a ship-breaking yard at Rincon Point at the southern end of Yerba Buena Cove, near the current anchorage point for the Bay Bridge. A man named Charles Hare ran a lucrative salvage operation here, employing at least 100 Chinese laborers to take old ships apart. Hare sold off brass and bronze fixtures for use in new ships and buildings. Scrap wood was also a valuable commodity in those days, Everett says.

The 1851 fire ended Hare’s business. Archaeologists have found the remnants of six ships at the site that were presumably in the process of being salvaged at the time of the fire. One—the Candace—was another whaling vessel pressed into service to bring gold-crazed prospectors to San Francisco. A lighter, small, flat-bottomed boat that was used to shuttle goods from moored ships to shore has also been found.

A development project near Broadway and Front streets, which began in 2006, turned up bones that archaeologists suspect came from Galapagos tortoises (the site is marked by an asterisk in the map at the top of this post). After passing around Cape Horn, many ships stopped in the Galapagos Islands and threw a few turtles in the hold—a source of fresh meat for the long voyage north to California. “They got to San Francisco, and lo and behold: They had more turtle than they could eat,” Everett says. Menus from the era show that turtle soup was a common offering at restaurants and lodging houses around the cove.

Illustrator and designer Michael Warner says his inspirations for the new map included the “Maps of Discovery” from a mural painted by N.C. Wyeth in 1928 for the headquarters of the National Geographic Society. Wyeth’s imaginative painting evokes the romance of the Age of Discovery, and Warner says it inspired him to go beyond just showing the details of the buried ships and historic wharves. “My hope is that I have not only enhanced the image for the history enthusiast,” he says, “but created something that might even make people learn by accident!”

The team is still ironing out some final details, such as how to most accurately represent the boundaries of Charles Hare’s ship-breaking yard. They hope to have posters of the new map available for purchase early next year and plan to eventually put it on display in the visitors’ center.