By KATIE LAUER | klauer@bayareanewsgroup.com | Bay Area News Group

PUBLISHED: July 12, 2023 at 9:00 a.m. | UPDATED: July 12, 2023 at 9:28 a.m.

Alex Hruzewicz mentally juggles dozens of ever-changing questions while skippering a 41-foot keelboat named Believe along the San Francisco Bay.

What’s the best moment to unfurl sails in 15 knot winds? How fast are the currents moving? Is there enough clearance for the rudder? Are any ferries barreling towards the boat? Will the tides be high enough to dock? Is there enough pressure on the lines?

“It’s a dance with Mother Nature,” Hruzewicz said, tacking into the shifting gusts using the boat’s electric winches as he sails back to Pier 40 at the Embarcadero. “You can play with the wind and waves. There’s an adrenaline rush and a peacefulness — there’s not much like it.”

After growing up around boats in Poland, he spent years working on commercial waters along the East Coast and picking up sailing delivery gigs. But after he broke his spine and both legs in a serious accident, he questioned if he would ever be able to sail again.

Fortunately, the Bay Area Association of Disabled Sailors (BAADS) works to ensure that the answer is always “yes.”

Since 1989, the nonprofit has offered hundreds of rides on specialized boats, specifically designed and adapted to accommodate different sailing abilities, in the South Beach Marina harbor. By 1992, the organization had adopted a new pirate mascot, embracing the legacy of the “original disabled sailors” who utilized eye patches, peg legs and hooks for lost hands.

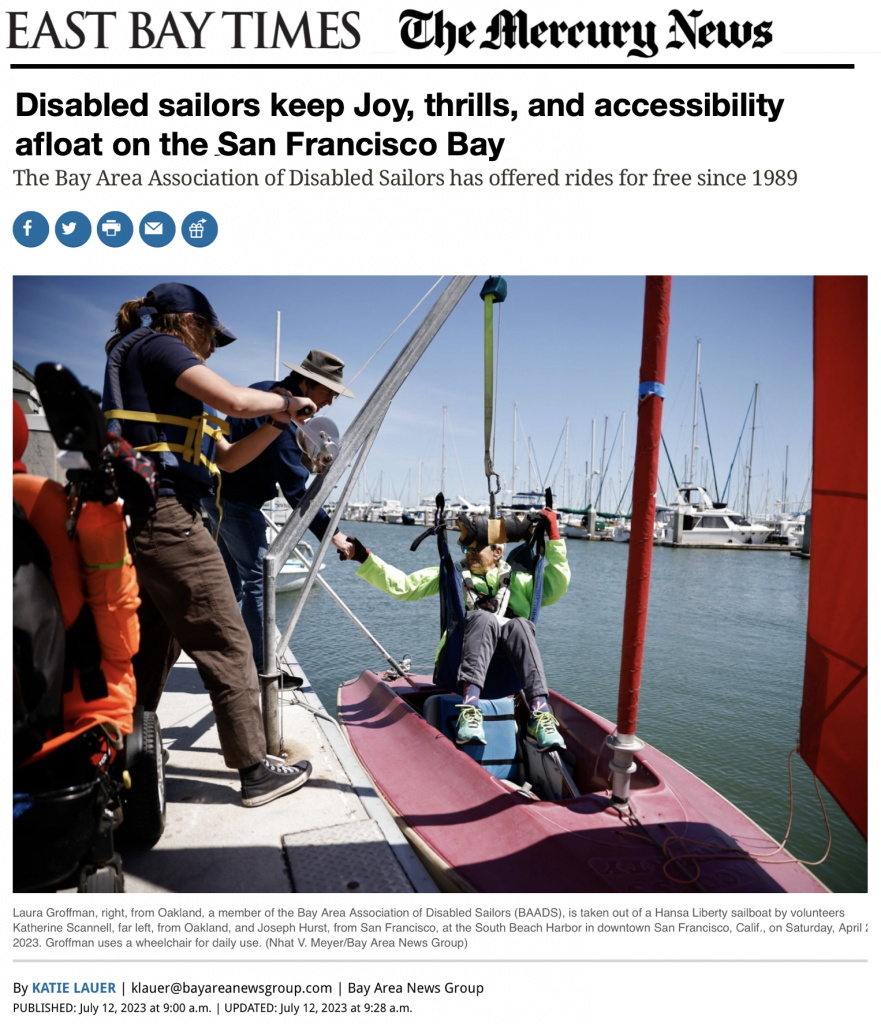

Whether someone is paralyzed or blind, an amputee or contending with neurological disabilities, BAADS has a trove of electric servos, winches and joysticks to help control the boat’s mainsheet and jib. There are harnesses and swing lifts to get sailors into the boats, as well as gimbaled seats and cushions to ease the toll of the windy ride. And able-bodied volunteers and guests help coordinate and set up the sailboats. The organization’s events are open to the public free of charge, offset by voluntary $60 annual memberships.

Kathi Pugh, BAADS’ current commodore, grew up swimming, playing water polo and sailing with her father. After a skiing accident paralyzed her from the chest down, sailing out into the middle of the Bay with BAADS has provided an exhilarating escape from daily life and the limitations that can come with using a power wheelchair — something she previously thought there was “no way” to accommodate.

“For someone like me, there were very few recreational opportunities available and nothing that was adventurous, had a little bit of danger or a thrill, and also took skill,” Pugh said. “After my first trip sailing around Angel Island, I thought, ‘Oh my gosh, my world has been rocked and will never be the same.”

She wanted to help share that exact feeling with as many people as possible and make all aspects of sailing accessible. Despite the popular belief that sailing is reserved for wealthy, privileged and able-bodied people, Pugh said, BAADS’ mission is simple: “Get butts in boats.”

Curious about taking a leisurely cruise beneath the Bay Bridge, where the roar of traffic above falls silent and you might even spot the troll hidden by ironworkers to protect the structure from earthquakes? On Sundays, there are five different keel boats — including the Believe, Flying Fog and Tashi — available for that excursion.

What about a more hands-on sailing experience, independently controlling a boat, up close and personal with the saltwater? More than two dozen dinghies are available on Saturdays, all designed and tested so they may heel but won’t tip over, even in the strongest winds.

BAADS’ opportunities have come a long way since the program first launched in Oakland, acting as the open water arm of the Lake Merritt Adapted Boating Program. Since then, the organization has trained scores of skippers, sponsored racing teams and hosted national championship races on the bay.

A slew of personal donations of adapted sailboats — often worth hundreds of thousands of dollars — and grant funding has helped keep BAADS afloat, allowing its more than 200 members and newcomers, alike, to feel the freedom of the open water nearly every weekend.

“I just leave my disability with the wheelchair on the dock,” Pugh said. “When I’m out there, I’m just so free. It’s just a thrill and a challenge in a whole different way. I feel such a kinship with the water — being both a Pisces and an adrenaline junkie — so being able to sail is just wonderful.”

Sailors and newbies alike come from across the Bay as well as Fresno and Sacramento to go boating, many of whom have never sailed before.

“But we also have a really good core group that is committed to sail every weekend they possibly can,” Pugh said. “One really great thing about sailing is if you really want to take it to another level, you can. Once you start getting more education and more experience, the world is really your oyster. It’s really fun to have a sport that also stimulates you intellectually.”

Cisco Ramos has taken that to heart, diving head first, so to speak, into several opportunities he would never have had without BAADS.

Starting in 2010, Ramos began feeling symptoms of what would later be diagnosed as multiple sclerosis. It eventually forced him to leave his heavy maintenance job in San Francisco and transition into his new normal of early retirement.

While the idea of even being out on the water used to scare Ramos, a Facebook invite to a BAADS excursion eventually pushed him to step out of his comfort zone — a life changing decision. He has since sailed down to Mexico, co-founded Sail MS, led small boat trips out of the Richmond Yacht Club and sailed internationally with Oceans of Hope.

Ever since his first trip with BAADS, sailing has become a source of both mental and physical therapy — helping him transition into a “new normal,” find empowerment and courage, listen to his body’s intuition, connect with community and find relief from the pain of living with MS.

“I push myself to get out to the docks, get on the boat and sail alone for a while; by the time I start heading back home, all my symptoms are gone,” Ramos said. “A few years ago, I’d never been on a sailboat, and I barely knew how to swim, but when I had the opportunity, I thought, ‘What do I have to lose?’